Монголын эзэнт гүрэн - Бага хаадын үе

XIY зууны үед Юань гүрэн задран унаж монголчууд хятад дахь ноёрхлоо алдсан боловч урьдын эрх мэдлээ сэргээх гэж хэдэнтээ оролдоод бүтээгүй билээ. Харьцангуй богино хугацаанд олон хаад солигдож байсан бөгөөд тэдгээр хаадын зарим нь улс орноо бүрэн дүүрэн төвлөрүүлэн захирч хараахан чадахгүй байлаа. Эл үеийг Монголын түүхэнд Бага хаадын үе хэмээн нэрийддэг ба улс төр эдийн засгийн хямрал ихээхэн нөлөөлжээ. Бага хаад болон том ноёдууд их хааны төвлөрсөн засаглалаас аль болохоор зайлсхийн эрх мэдлийн төлөө бие даах гэж оролдсон тэр үеийг Монголын бутралын үе гэж түүхэнд нэрлэжээ. Улмаар 1372 онд хятадын 15 мянган цэрэг Монголд довтолж, 1380 онд Мин улсын цэрэг Хархорум хотыг шатаажээ.

Мин улсын эрх баригчид Монголын бага хаадын дунд яс хаяж хооронд нь дайтуулсаар хүчийг нь сулруулаад өөрсдөө довтолдог уран нарийн аргатай болсон байв. 1409 онд Ойрад болон Зүүн Монголын байлдаанд Мин улсын цэрэг Ойрадад туслан Зүүн Монголыг цохиж байсан бол 1413 онд Зүүн Монголд туслан Ойрадын цэргийг ухрааж байжээ. Тэр үеийн монголчууд нь Мин улстай эдийн засгийн талаар өргөн харилцаж янз бүрийн эд барааг малаас гардаг түүхий эдээр сольж авдаг байв. Харин Мин улсын тал өөрийн оронд ирэх монголын худалдаачдын тоог хязгаарлах, хилийн боомтын худалдааг хаах, монголын мал түүхий эдийн үнийг бууруулах зэргээр дарамт шахалт үзүүлдэг байсан учраас монголчууд хятадын хилд удаа дараа довтолдог байжээ. 1449 онд Эсэн тайш Мин улсын их цэргийг бүслэн бут цохиод Ин Цзун хааныг олзлон авчээ.

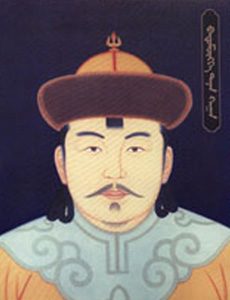

Олон жил үргэлжилсэн Монголын улс төрийн хямрал нь 1467-1543 он буюу Батмөнх Даян хааны үед намжиж, бүх Монголыг нэгтгэсэн юм. Батмөнх 1480 онд хаан ширээнд сууж Мандухай хатны хамт эхлээд Зүүн Монголчуудыг нэгтгэн эе эвийг олоод дараа нь Дөрвөн Ойрадыг байлдан эзэлж захиргаандаа оруулжээ. Зарим өөрчлөлтийг хийж “тайж”-ийн оронд “жонон” гэдэг тушаалыг бий болгон Зүүн Монголын Зүүн түмнийг өөрөө захиран Баруун түмнийг жонон захирдаг болгожээ. Их Монгол Улсын үед нийгмийн зохион байгуулалтын үндсэн хэлбэр нь мянганы тогтолцоо байсан бол XY зууны эхэн үеэс том ноёдын эзэмшил нь “отог” хэмээх шинэ зүйл бий болж, тодорхой газар нутаг, тэнд амьдрах малчин ардууд, тэдний мал хөрөнгөөс бүрдэх болжээ. Батмөнх хаан Мин улстай найрамдалт харилцааг хадгалахыг хичээж тэр завсартаа дотоод асуудлаа амжилттайгаар цэгцэлсэн юм. Түүхэнд Батмөнх Даян хаан, Мандухай сэцэн хатны үед монголчууд өвөр зуураа дайн байлдаангүй түр амсхийж ард иргэд нь хэсэг хугацаанд ч болов амар тайван амьдарсан хэмээн тэмдэглэжээ.

Олон жил үргэлжилсэн Монголын улс төрийн хямрал нь 1467-1543 он буюу Батмөнх Даян хааны үед намжиж, бүх Монголыг нэгтгэсэн юм. Батмөнх 1480 онд хаан ширээнд сууж Мандухай хатны хамт эхлээд Зүүн Монголчуудыг нэгтгэн эе эвийг олоод дараа нь Дөрвөн Ойрадыг байлдан эзэлж захиргаандаа оруулжээ. Зарим өөрчлөлтийг хийж “тайж”-ийн оронд “жонон” гэдэг тушаалыг бий болгон Зүүн Монголын Зүүн түмнийг өөрөө захиран Баруун түмнийг жонон захирдаг болгожээ. Их Монгол Улсын үед нийгмийн зохион байгуулалтын үндсэн хэлбэр нь мянганы тогтолцоо байсан бол XY зууны эхэн үеэс том ноёдын эзэмшил нь “отог” хэмээх шинэ зүйл бий болж, тодорхой газар нутаг, тэнд амьдрах малчин ардууд, тэдний мал хөрөнгөөс бүрдэх болжээ. Батмөнх хаан Мин улстай найрамдалт харилцааг хадгалахыг хичээж тэр завсартаа дотоод асуудлаа амжилттайгаар цэгцэлсэн юм. Түүхэнд Батмөнх Даян хаан, Мандухай сэцэн хатны үед монголчууд өвөр зуураа дайн байлдаангүй түр амсхийж ард иргэд нь хэсэг хугацаанд ч болов амар тайван амьдарсан хэмээн тэмдэглэжээ.

Батмөнх Даян хаан өөрийн 11 хөвгүүндээ газар нутгаа хуваан өгчээ. 11 хөвгүүдийн 7 нь Мандухай хатны, 4 нь бага хатан Жимсгэнийнх ажээ. Ууган хүү Төрболд эцгээсээ өмнө нас барсан, удаах хүү Улсболд 1500 онд Ибрай тайшид алагдсан, гутгаар хүү Барсболд жононд өргөмжлөгдсөн, дөтгөөр хүү Арсболд Түмэдийн 7 отгийг захирдаг, тавдугаар хүү Очирболд нь Цахарын 8 отгийг, зургадугаар хүү Алчуболд нь Халхын өвөр 5 отгийг, долдугаар хүү Арболд нь Цахар болон Хуучидын 2 отгийг, наймдугаар хүү Гаруудай нас барсан бол, есдүгээр хүү Гэрболд нь Ахан болон Найманы отгийг, аравдугаар хүү Увсанз нь Юншөөбү отгийг, отгон хүү Гэрсэнз нь Халхын 7 отгийг тус тус захиран суужээ. Ууган хүү Төрболдын хөвгүүн Боди Алаг нь Их Монгол Улсын хаан ширээнд суухдаа Цахаруудын нутагт төвлөн сууснаар хаан ширээ, төрийн тамга нь Монголын өмнөд хэсэгт шилжсэн байна. Эл үеэс өвөрлөгч хэмээх нэр томъёо үүсчээ.

1640 онд Ойрадын Эрдэнэбаатар хунтайж Тарвагатайн нурууны Улаан бураа хэмээх газарт Монгол ноёдын чуулган хийхийг санаачилснаар Халх болон Ойрадын 28 томоохон ноёд оролцсоны дотор Засагт хан Субадай, Түшээт хан Гомбодорж, Ойрадын Эрдэнэбаатар хунтайж, Увш гүүш хаан Төрбайх, Хөх нуур, Ижил мөрний Торгууд нарын төлөөлөгч, Халх Ойрадын шашны зүтгэлтнүүд оролцжээ. Чуулганаар “Дөчин дөрөв хоёрын их цааз” гэдэг 120 зүйл бүхий хуулийг баталж, Манжийн эзлэн түрэмгийллийн эсрэг бүх нийтээрээ тэмцэх, буддын шашны шарын урсгалыг улсын шашин болгож түүний дэмжлэгээр Монгол овогтныг нэгтгэх, том ноёдын зөрчил сөргөлдөөнийг зогсоож хүчээ төвлөрүүлэх зэрэг асуудлуудыг хэлэлцсэн байна. Эл хуулийн үзэл санааг Эрдэнэбаатар хунтайж, Зая бандидаа Намхайжамц нар идэвхтэй хэрэгжүүлэн Ойрадын дотоод зөрчлийг зогсоож, аж ахуйгаа сайжруулж, Орос, Казах зэрэг улстай харилцаа тогтоожээ.

Дундад зууны хоёрдугаар хагасын үед Халх, Ойрад, Цахар буюу Ар Монгол, Баруун Монгол, Өвөрлөгч Монгол гэж хуваагдсан байжээ. Ар Монгол буюу Халх нь 3 хантай, Чингис хааны цагаан сүлдтэй голомт нутаг боловч аль нэг нь товойн гарч чадахгүй байсан учраас шашнаар дамжуулан нэгтгэхийг оролдон 1639 онд Анхдугаар Богд нэрээр хаан тодруулан залсан бол Өвөрлөгч нар угсаа залгамжилсан Лигдэн хаанаас хойш тэргүүлэх удирдагчтай, харин Баруун Монгол нь Эрдэнэбаатар хунтайжийн захиргаанд байв.

Ар Монголд Түшээт хан Гомбодоржоос хойш Галдан, Занабазар нарын тэмцэл хурцдаж, Халхын ноёдоос хамгийн түрүүнд Түшээт хан Гомбодоржийн хүү Бундар 1673 онд эцгийгээ нас барахаас 2 жилийн өмнө харъяат ардаа авч Манжид урваж “Засаг чин ван” цол хүртсэн түүхтэй ажээ. Ийнхүү манж нар ямар ч гарз хохиролгүйгээр хэдэн хоосон цол хэргэм, чулуун шигтгээ, шувууны өд, торго даавуугаар монголын ноёдыг өөр хооронд нь өрсөлдүүлж, эд хөрөнгөөр уралдах, атаархаж жөтөөрхөх үзлийг дэгдээж түүнийхээ үр дүнд ямар ч төвөггүйгээр Халхыг өөртөө урвуулан авч эзэлсэн гашуун түүхтэй юм.

Эх сурвалж: Монгол орны лавлах

While Kublai Khan and his successors were relishing their luxurious sedentary lifestyle in Beijing, resentment constantly simmered back in the Mongolian heartland, first over Kublai’s controversial accession as Great Khan and then his shift of the Mongol capital from Karakorum into China, a move seen as abandoning his own heritage.

Mongol warriors openly rebelled against Kublai. From farther west, Ogodei’s grandson Kaidu, angry at losing his heritage, started a rebellion that briefly occupied the old capital at Karakorum. Ordinary people also frequently revolted as the homeland was depleted and demoralized. With the collapse of the empire a tragic sequence of spilled blood and shattered hopes ensued, and things would barely improve over the coming centuries.

With the fall of the Yuan Dynasty in 1368, Mongolia reverted to a lengthy period of feudal separatism and rivalry for control of the khan’s throne. Some 60.000 Mongols fled north with Emperor Tongoontomor, while many stayed behind to serve the Ming Dynasty, often in military units. (Others were actually prevented from leaving China, such as a small community of Mongols whose descendants remain in Yunnan Province to this day.)

Now rebadged as the Northern Yuan Dynasty, the Mongols staggered on with an increasingly acrimonious succession of leaders, all claiming links back to Genghis Khan himself – and the right to recreate the empire. The Ming Chinese had attacked from the south, sending the last Yuan Emperor and his followers fleeing north into a Mongolia that, in those days, began just over the Great Wall in today’s Inner Mongolia region of China. It wasn’t long before the new Chinese dynasty launched a series of brutal invasions into the Mongolian heartland, culminating in the sacking of Karakorum in 1388 and the capture of 70.000 troops. Other cities were also destroyed.

Rather than outright occupation, the Ming Dynasty’s objective was to batter and weaken the Mongols and prevent their resurgence, a policy that also included “economic warfare”. Aware of the nomadic Mongols’ long-time reliance in sedentary societies for certain goods, such as silk, iron and grains, the new dynasty in Beijing imposed a trade embargo.

Increasingly, the Mongols retreated back into subsistence-level herding and built up their military strength for raids on China’s sedentary populations for the goods they needed. The more peaceful alternative, of course, was trade. But here, the Mongols were at the total mercy of the Chinese, not only on costs but their divide-and-rule tactics. And as, we shall see, the ultimate price for the Mongols in this endless game would be face-losing “vassal status” – one chunk at a time – to its more powerful neighbor.

The endless battles continued. The Ming never got a foothold and the Mongols always expelled them, even staging the odd raid – including famously kidnapping on Ming Emperor – back into their old stomping grounds. The Ming would find little peace from the scrappy Mongols for the entire duration of their dynasty. Its no wonder the Great Wall underwent its grandest renovations- including its present brick and stone facade – during this period. (And when the Ming did fall, someone simply opened the gate to the Manchu from the northeast.)

Among what we’ll now call the Mongolians (rather than Mongols, given the diversity of the region’s tribal groups), the most disturbing – and ultimately self-defeating-development was their rapid reversion to the tribal divisions of the past (it certainly sanctifies the sheer genius of Genghis Khan in having surmounted these to create his empire). By the early 15th century, a civil war had broken out between the Halh of central and eastern Mongolia and the Oirads of the western Altai Mountains. The battle was also between what are called the Genghisids, those claiming links back to the Great Khan, and the non-Genghisids.

The Oirads had sat out the Yuan Dynasty, even supported the anti-Kublai rebels, and were in a strong economic position from their strategic location along the Silk Road. They now renounced the Mongol Empire’s khans, whose remnants ruled the Halh, and the struggle for power between the two parts of Mongolia began. With the Chinese-and later the Russians-contributing their divide-and-rule tactics, the struggle between the country’s east and west would continue for centuries and remains very much in the public memory today.

In the first half of the 15th century, the Oirads were clearly in the ascendancy and brought most of greater Mongolia under their control. In 1449, after attempts to establish normal trading relations failed, Esen Taishi invaded China and in a battle against a superior Chinese force actually captured the young Ming Emperor Zhengtong and held him hostage. But any hopes the Oirad leader had of a ransom – much less normal relations – collapsed when his brother took over as emperor and refused to negotiate. Zhengtong was held for another four years, regained the throne and heavily purged Mongols still serving in Chinese units. Esen Taishi was soon overthrown by his own supporters.

Power now switched eastwards to the Halh with the legendary story of Mongolia’s own Joan of Arc, Queen Manduhai the Wise, khan’s widow who adopted and later married Kublai’s last surviving descendant, five-year-old Batu Mongke, to keep the lineage alive. Acting as regent, she then defeated the Oirads and reunified a Mongolia that spread into Central Asia. Also known as Dayan Khan, her now-husband ruled from 1470 to 1543 and was one of the longest ruling post-Empire khans. But after his death, the country again fell into disarray, now a land of many khans.

Among the warring factions was Batu Mongke’s grandson. Altan Khan, who ruled over the Tumed in today’s Inner Mongolia and was best known for introducing the now-dominant Yellow Hat form of Tibetan Buddhism into Mongolia in 1578. Then still a minority sect back home, Altan Khan coined the title “Dalai Lama” – or “ocean lama” – for its leader and in return was conveniently recognized as the reincarnation of Kublai Khan. With other local rulers soon scrambling to convert and also gain similar recognition, Altan Khan’s move re-established Buddhism and created a path that would lead to the religion dominating Mongolia’s political, social and economic life.

(In fact, the Yellow hat sect gained such fervent support in those support in those early days that Mongolian troops invaded Tibet to overthrow the dominant Red Hats. Today’s Dalai Lama, also deeply revered in Mongolia, clearly owes his lineage to these 16th century Mongolians.)

At the same time, after a small incursion towards Beijing, Altan Khan was finally able to secure peace and normal trade with the Ming, who also allowed him to make Tibet a Mongolian sphere of influence. He established the city of Hohhot, or Blue City, the capital of today’s Inner Mongolia, and drove the Oirads out of Karakorum.

By the early 17th century, Mongolia had dozens of khanates and princedoms, each running their own agenda and obsessed with titles, first, from china and later from Tibet. The Dalai Lama also gave Altan’s brother the title of Tusheet Khan over Mongolia’s sacred heartland in the Orhon Valley, where he would soon establish the Erdene Zuu Monastery on the ruins of the Mongol Empire’s capital city. Not long after this in 1635 his grandson was born; the Dalai Lama proclaimed his the Buddhist reincarnation of Javzandamba, who would become First Bogd Javzandamba, or spiritual leader of Mongolia, but he was best remembered as Zanabazar.

In the Tibetan Buddhism hierarchy, Mongolia’s theocratic leader was the third-highest ranking incarnation after the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama. Quite conveniently, Mongolia’s own imperial family – that of Genghis Khan – was now tied into the highest ranks of the Buddhism hierarchy. The feudal lords hoped, as in Tibet, that this combination of the political and spiritual, or theocracy, would unify their country. The Ming and then the Manchu (Qing) saw the tie-up as a means of weakening and controlling the Mongolians. In the end, the consequences would be catastrophic and would last into modern times.

Resource: Carl Robinson 'Mongolia Nomad Empire of Eternal Blue sky"